How Scientists Explore the Darkest Depths Safely

The ocean floor is close to seven miles down in some places, a no man’s land of total darkness, imploding pressure and near-freezing temperatures. But researchers keep plunging into these inhospitable settings, where they find new species and learn about our planet’s secrets. How are they able to venture these perilous depths and come back unharmed? The solution combines high-technology and meticulous planning, not to mention decades of innovation in deep-sea exploration.

Exploring the deep seafloor isn’t just about curiosity. In the depths are answers to questions about climate change, medical breakthroughs and even the origins of life. Each foray into the abyss calls for skilled equipment and safety measures that shield researchers from conditions more extreme than those of outer space. Now let’s explore the dark abyss of our ocean, and see how scientists are daring to travel these great depths.

The Extreme Challenges Lurking Below

Before we’re able to understand how scientists safely probe it, however, let’s first take a look at what makes the deep ocean so perilous. It seems the environment down there is designed to eat anything not rooted.

Crushing Pressure That Destroys

Pressure of water continue to increase when the depth increases. The pressure increases by one atmosphere (14.7 pounds per square inch) every 33 feet you descend. At the very bottom of Earth — in the Challenger Deep in the Mariana Trench — pressure gets to about 16,000 pounds per square inch. That’s as if you had fifty jumbo jets resting on top of your thumb.

Human bodies aren’t built to endure all that force. Our lungs would collapse, our cells crushed. Even the hardiest military submarines can descend to only about 2,000 feet before their hulls face catastrophic failure.

Complete and Total Darkness

Sunlight can reach a maximum depth of about 650 feet in the ocean. And below about 3,300 feet is the midnight zone, where no direct light penetrates at all. Animals that live here have evolved bioluminescence — the ability to make their own light by way of chemical reactions. For humans, the visibility is always zero unless they are using very bright artificial lights.

Bone-Chilling Cold

Temperatures in the deep ocean are just above freezing, generally 32 to 39 degrees Fahrenheit. And without good insulation, hypothermia would quickly follow. Equipment also has to be able to endure those temperatures without becoming brittle or inoperable.

Toxic Environments and Unknown Dangers

Some deep-sea spots are filled with poisonous gases, water superheated by hydrothermal vents to 700 degrees Fahrenheit and methane seeps. Then there are the astronomers’ own unknowns: What might come nibbling while we’re out seeing the interstellar sights?

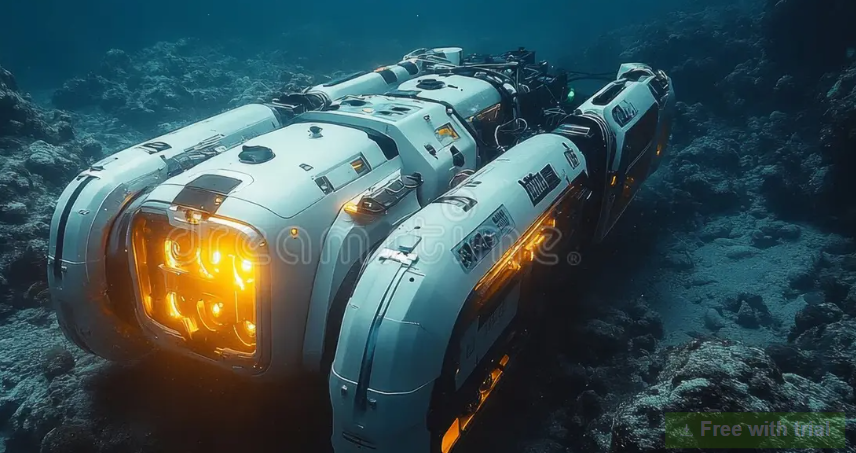

Submarines: Work Horses of the Deep

Of course, the primary equipment for humans to reach the depths of the deep-sea is the submersible – an aquatic spacecraft capable of withstanding intense pressures and providing protection for human crewmembers.

How Pressure Hulls Protect Explorers

Current submersibles utilize a pressure hull made of titanium or specialized steel. She’s completely spherical so the pressure and tension she exerts is on the whole surface, with no weak spots. The hulls are usually several inches thick, and undergo extensive testing before being set to sea.

The passenger sphere of a deep-sea submersible could be only six or eight feet in diameter, affording little room to move around. But this diminutive size is key — as with all things, the smaller the sphere, the greater the resilience against pressure. Up to 8-12 hours scientists could be spending inside them during a visit, if not one single dive.

Life Support Systems to Sustain Human Beings

Within the pressure hull, complex life support systems keep the air breathable, scrub carbon dioxide, and control temperature. Scrubbers incorporating lithium hydroxide or similar chemicals soak up the CO2 exhaled by crew. Oxygen tanks offer fresh air and backup systems have redundancy in case primary systems fail.

Temperature regulation requires careful balance. The chilly ocean waters are keen to draw heat from the hull, and electronic gear, human bodies all generate warmth within. Insulation and heat/cool systems keep it comfy.

Famous Submersibles and Their Capabilities

A few submersibles have attained iconic status for deep-sea exploration:

Alvin: Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution has used Alvin since 1964; it reaches depths of up to 21,325 feet and has conducted more than 5,000 dives. It first found hydrothermal vents in 1977, which changed our understanding of deep-sea ecosystems.

DSV Limiting Factor: This privately-owned submersible became the first of its kind to dive to the seven deepest points in all five oceans. It is rated for full ocean depth — nearly 36,000 feet.

Shinkai 6500: Japan’s dependable submersible can dive down to 21,325 feet and has mapped parts of the Pacific Ocean.

Jiaolong: China’s Jiaolong is a 23,000-foot-deep-sea vehicle and one more indication of that country’s increasing hand in ocean exploration.

Robots With a View: No Risk to Eyes

All exploration does not have to involve putting humans in harm’s way. Scientists explore from the safety of a ship on the surface with Remotely Operated Vehicles (ROVs).

Robots Tied by String, That Can Move Where Humans Can’t

ROVs are tethered to the surface ship via a wire, which supplies power and sends data. This tether normally includes fiber optics for high-definition video, copper wires for power and occasionally more lines for hydraulics.

With no life support equipment needed and the reduced need for same safety margins as would be required for a human crew, ROVs may also be more lightweight and operate at greater depths. And they can likewise remain underwater, sometimes for days or weeks, constrained only by the reliability of their equipment rather than human stamina.

Advanced Sensors and Sampling Tools

Today’s ROVs are equipped with an incredible range of scientific sensors:

- High definition and 4K cameras: Footage is captured using cutting-edge technology.

- Sonar Systems: Seafloor mapping and object detection in turbid water.

- Temperature, salinity and chemical sensors: Environmental inputs are received via these sensors.

- Manipulator arms: Used to collect samples, place instruments and conduct sensitive operations.

- Suction samplers: Take small animals without hurting them.

- Sediment corers: Taking sample tubes out of the deep-ocean floor.

Real-Time Decision Making

Or scientists on the surface can look through what ROV is seeing – with minimal delay – thanks to the fiber optic link. This real-time feedback allows researchers to make decisions on the fly — steering toward an interesting formation, for instance, or picking up a surprising specimen, or avoiding hazards.

The ROV is operated by pilots using joysticks and computer interfaces that make operating it a bit like playing a very expensive video game. But it is not like a game, where the only thing at stake is pride: Mistakes can result in millions of dollars’ worth of damaged equipment.

Autonomous Underwater Vehicles: Independent Explorers

AUVs are the latest in deep-water exploration technology. These are all free-flying robots that have been pre-programmed to guide their movements without any connection to the ground.

Freedom From the Tether

AUVs, unencumbered by a cable to the surface, are able to move more and faster than ROVs. They’re ideal for mapping large expanses of seafloor, performing surveys and exploring areas where a tether might become entwined or snagged.

AUVs are powered by batteries, this constrains their duration of the mission. They can operate for 12 to 24 hours before they need to go back and recharge. But certain specialized AUVs can work for months on end thanks to advanced battery technology or alternate power.

Navigation in the Darkness

GPS signals do not travel under water, so AUVs cannot depend on satellite navigation the way surface vessels can. Instead, they rely on:

- Inertial navigation systems monitoring each step

- Doppler velocity logs providing estimates of seafloor speed

- Acoustic Positioning from Surface Ship using USBL

- Obstacle avoidance with the sonar for a terrain following algorithm

Programming Intelligent Behavior

Today’s AUVs can even make simple decisions on its own and free of human intervention. They could also autonomously adapt their altitude to the seafloor topography, detect and circumvent obstacles or maybe even identify points of interest and acquire more data.

Some experimental AUVs are programmed with artificial intelligence to recognize geological formations or marine life, so that they can zero in on scientific targets.

Atmospheric Diving Suits: Personal Submarines

At greater depths than can be safely visited by scuba diving but less than where submersibles are practicable, so called atmospheric diving suits (ADS) can provide an alternative.

Maintaining Surface Pressure at Depth

An atmospheric diving suit, he explained, is basically a wearable submarine. It keeps an atmosphere of pressure while at depth, therefore equals the surface so no change in pressure is experienced regardless of depth. This eliminates the bends and permits immediate return to the surface.

Today’s ADS can dive as deep as 2,000 feet and permit divers to work for hours. The most well-known of these, the Exosuit, looks like a cross between a heavily armored spacesuit for diving and one of Iron Man’s astro-togs, complete with articulated joints that grant surprising mobility.

Advantages for Hands-On Work

ADS involves putting a person in communication with the work site, while ROVs require remote control. Divers can make split-second choices, handle fragile items and improvise in new surroundings in ways that robots are not yet able to. The human touch contributes a flexibility that pure automation has yet to duplicate.

Limitations and Risks

ADS are costly to install and support, and can only function within modest depth ranges. The suits are also bulky, and vulnerable to snags on underwater structures. Should the diving suit become flooded or deflated, he is immediately threatened by both pressure and cold.

Safety Protocols That Save Lives

Technology alone doesn’t ensure safety. Stringent protocols and procedures provide protection to scientists at all levels of exploration.

Pre-Dive Checklists and Inspections

Before any dive, teams spend hours checking over every system. Checklists that cover hundreds of items make sure nothing is missed:

- Integrity of pressure hull and condition of viewports

- Life Support System and Redundancy

- Communication equipment and emergency beacons

- Ballast arrangements and emergency drop weights

- State of charge and power splitting of battery

- Manipulator arms and sampling equipment

- Cameras, lights, and scientific instruments

Redundancy in Critical Systems

Every critical system has backups. Submarines are equipped with multiple O2 supplies, redundant CO2 scrubbers, backup power systems and spare communications gear. Other systems quickly substitute if one system fails.

The thinking is straightforward: Plan for something to fail, and don’t let that failure be catastrophic.

Emergency Procedures and Rescue Plans

All dive projects involve extensive emergency procedures and contingency planning. Tender boats took backup equipment and personnel trained in underwater rescue from support ships. In the deep sea, rescue submersibles are available to aid disabled ships.

Submersibles carry emergency systems like:

- Releasable drop weights for positively buoyant vessel

- Acoustic beacons that are activated in case communication is interrupted

- Life-support extension technologies that can stretch what would otherwise be hours of air into days

- Emergency lighting and backup power

- Attachment lines and recovery points

Communication Protocols

The dive team’s status is constantly monitored with regular check-ins to the surface. When communication is interrupted, pre-determined protocols are automatically initiated. The submersible could have automatically resurfaced, or the surface team could have dispatched rescue assets.

Acoustic communication is viable underwater, but with restrictions. Slower and with lower bandwidth than radio messages, but a vital lifeline between depth and surface.

Training: Preparing for the Unexpected

The humans who plumb the deep train intensively to handle normal operations and emergencies.

Simulator Training

Long before they slip inside an actual submersible, pilots and scientists practice in state-of-the-art simulators. These resemble the tight quarters, control interfaces and even emergency scenarios they might encounter out there. Simulator sessions — involving hundreds of hours, drilling down responses until they are instinctive — may be stretched more thinly.

Emergency Response Drills

Training includes scenarios like:

- Fire in the pressure hull

- Loss of power or life support

- Entanglement in underwater obstacles

- Medical emergencies at depth

- Communication failure

- Flooding or pressure loss

Crews repeat these scenarios until they can react efficiently even under pressure and fatigue.

Physical and Psychological Preparation

Deep-sea diving is tough and lonely. Scientist-pilots are tested for fitness and undergo psychological screening. In confined, dark emergency situations, steadiness is key.

Some tasks involve showing we can stay functional for days in small spaces, making decisions with pressure and the stress of being in a challenging environment.

Mapping the Unknown Floor

Before they dispatch people and expensive equipment to the deep, scientists map the seafloor with technologies that operate from the surface.

Multibeam Sonar Systems

Nowadays, the sound pulses are transmitted in fan-shaped arrays by multibeam echo sounders on modern research vessels. Computers use the time it takes for each pulse to bounce back — combined with speed information and precise location data for the source of transmitted sound — to draw detailed three-dimensional maps of the seafloor.

These systems can map the ocean floor in water as deep as thousands of feet at a resolution that’s high enough to discern objects the size of a car. The mapping uncovers undersea mountains, canyons, submarine volcanoes and hazards before divers splash in for dive operations.

Seafloor Mapping Table

| Technology | Maximum Depth | Resolution | Primary Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multibeam Sonar | 36,000+ feet | 3-30 | Wide-area seafloor mapping |

| Side-Scan Sonar | 20,000+ feet | 1-3 | Detailed object detection |

| Sub-Bottom Profilers | 15,000 feet | 1-6 | Seeing beneath seafloor |

| LiDAR (in clear water) | 300 | Inches | High-resolution shallow mapping |

Satellite Altimetry

In fact, satellites can measure ocean depth from space by observing small differences in the sea surface. The gravity of underwater mountains produce small bumps on the ocean surface. While this technique doesn’t offer sonar’s detail, it can help identify broad features and point to areas to be closely studied.

Supporting Technology on Surface Ships

These surface vessels are key to ensuring the safety of deep-sea activities.

Dynamic Positioning Systems

Research vessels maintain precise positions at sea without relying on anchors thanks to DP. GPS and acoustic beacons inform the ship of its location, and computer-controlled thrusters are used to automatically compensate for wind, waves, currents.

This accuracy is critical during submersible or ROV use. It runs on a tether, so if the ship drifts, the tether may tangle or drag the submersible off course.

Launch and Recovery Systems

Deploying submersibles and ROVs safely, in and out of the water, involves specialized equipment. Launch systems include:

- A-Frames/Cranes to bear the weight of the equipment

- Wire guides that prevent swinging in a chop

- Lifting cables with quick release connectors

- Deck crews, who are trained in the safe manual handling of materials

The safety during launch and recovery is highly dependent on the sea conditions. Most activities are restricted to sea states below a certain cutoff — usually waves of less than six feet.

Weather Monitoring and Forecasting

And our surface teams are always monitoring the weather. Even when a submersible is thousands of feet down, surface storms can make recovery treacherous. An operation could be postponed or even called off according to weather predictions.

Studying Life in Extreme Conditions

One of main objectives of deep-sea research is to investigate those distinctive organisms in these extreme habitats.

Bioluminescent Creatures

Of all the creatures that live in the dark, about 90% are known to be bioluminescent. They employ this capability to lure in prey, communicate, bewilder predators and discover mates. Special cameras and filters that can be used to observe these light shows allow scientists to study them without blinding everything in the area with bright artificial lights.

Hydrothermal Vent Ecosystems

In 1977, Alvin found hydrothermal vents — suboceanic hot springs inhabited by complex ecosystems in total darkness. Instead of using sunlight and the process of photosynthesis, which is currently our best guess as to how other life forms use chemical energy, these communities rely on a process called chemosynthesis in which bacteria turn chemicals from the vents into food.

Clusters of giant tube worms, eyeless shrimp — and other strange creatures out there swarm those vents. Investigating these ecosystems safely needs heat-resistant equipment and delicate approach maneuvers to prevent disturbing the fragile communities.

Sample Collection Without Contamination

Deep-sea sampling is difficult. Bringing them to the surface puts them through dramatic pressure changes that often kill them. Scientists use:

- Pressure hulls which maintain depth pressure while a vessel resurfaces

- Containers that are temperature-controlled to maintain the samples cold

- Chemical preservatives to fix specimens immediately

Yet there is a need for more time-sensitive collection protocols to reduce stress on living samples.

Medical and Scientific Benefits

The risks of deep-sea exploration are rewarded with discoveries that can help humanity.

Biomedical Discoveries

Deep-sea life produces novel compounds that have medical potential:

- Stronger than morphine painkillers

- Anti-cancer compounds from deep-sea sponges

- Antibiotics that fight drug-resistant bacteria

- DNA analysis and biotechnology enzymes

Understanding Climate Change

Not only that, but the deep ocean is one of our critical regulators of climate. It sucks enormous amounts of carbon dioxide and heat from the air. Understanding climate change: By learning about deep currents and temperature and chemical changes in ocean waters, scientists can figure out more about the Earth’s changing climate and improve predictions.

Geological Research

The history of the planet is etched into the seafloor. These sediment cores can contain layers of sediment that go back millions of years, providing glimpses into long-ago climates, volcanic eruptions and even asteroid impacts.

The Future of Deep-Sea Exploration

Technology is always advancing, and new promises of safer and more capable exploration tools are common.

Hybrid and Autonomous Systems

The next-generation of vehicles will be a mix between ROVs and AUVs. They could run more or less by themselves for long periods but can also be directed when we comes across new and interesting data.

Artificial Intelligence Integration

AI will be used to locate interesting features, steer clear of hazards and even make decisions about where to focus research. Machine learning algorithms can pore through hours of video footage, flagging anything strange-looking for human review.

Improved Materials Science

New materials, such as carbon fiber composites and advanced ceramics, could enable submersibles to dive deeper than ever before with less weight and added strength. Such materials could allow human exploration of parts of the ocean that are currently out of reach.

Networked Exploration Systems

Future missions could use fleets of coordinated robots, rather than individual vehicles. Why swarms? Swarms of small AUVs can map large regions rapidly, while other, more capable craft explore interesting subjects. This networked method leads to both increased efficiency and redundancy.

Frequently Asked Questions

What if a deep-sea submersible becomes trapped under water?

Submersibles are equipped with emergency drop weights — heavy ballast that can be jettisoned instantly to raise the vessel up. If all else fails, mechanical releases will use links that corrode away on triggers every 24-72 hours. Disabled ships can also be helped by rescue submersibles.

Can people breathe at the bottom of the ocean without a sub?

No. The pressure at such a depth would immediately crush a human body. In even shallow water (say, a few hundred feet), it would need complex underwater gear. The greatest depth to which a person can safely descend with regular scuba equipment is about 130 feet, and the record for the deepest dive using special gas mixtures is around 1,000 feet — nowhere near what’s found in the ocean’s darkest depths.

How long can people live in a deep-sea submersible?

Most science dives are for 8-12 hours, but the life support systems can generally endure for 72-96 hours in an immediate emergency. The limitation is usually the battery and a human being rather than an air supply. Some submersibles are equipped with enough oxygen to last for four to five days, if necessary.

Why not use submarines to explore the deep seas?

As the name suggests, these military submarines are made for other purposes and cannot cope with deep-ocean pressures. Almost no submarines ever go below the 800-2,000 foot range in depth. Submersibles for research are designed for extreme depths, with pressure hulls and features that military submarines don’t need. The tech and design are entirely different.

How do scientists see in the pitch-black of the deep ocean?

Submersibles and ROVs are equipped with bright LED lights. They can be dimmed or screened so that the creatures accustomed to darkness are less disturbed. Some cameras can even record the faint bioluminescent glimmer given off by deep sea organisms without any added illumination.

How deep have humans been able to explore?

The lowest place on Earth is Challenger Deep in Mariana Trench about 36,000 feet below sea level. The film director James Cameron reached its depth in 2012, and the businessman Victor Vescovo has made several descents to the bottom. Few have ever reached this dramatic extreme depth.

Wrapping Up the Journey

Visiting the very bottom of the ocean is a challenge, depending on more than engineering, and ventures require extraordinary human courage and determination as well. From pressure hulls strong enough to resist crushing, to robotic operability that allows exploration in areas where men cannot safely venture, the focus of deep-sea exploration is first and foremost on the safety of researchers while simultaneously extending our knowledge.

The abyss is one of the least studied habitats on earth. We know more about the Moon and Mars than we do about our own seafloor. But every journey there also helps unlock treasures — new species, geological marvels or clues to how our planet functions. The findings from these challenging environments lend support to medicine, climate science and enhance our basic comprehension of life.

For success stories, if we keep making technological progress, exploration becomes a lot safer and easier. It once demanded vast government funding and military submarines, it is now achievable by smaller research groups using more sophisticated equipment. The next generation of ocean explorers will have better tools than their forebears could ever dream up, unlocking more and more of the ocean’s secrets for science.

The safety measures, technologies and protocols that have been developed specifically for deep-sea exploration safeguard not only scientists but also stimulate innovation in myriad other ways. From the pressure hulls of submersibles, to material that protects us from hostile environments, to equipment used in space and recovery and exploration, deep-sea technology has potential uses for space travel, disaster response and everyday life.

And like the light-hoarding fish in the deep, we head further into the abyss fueled by curiosity and protected by updated safety protocols. Each dive of technical divers is a risk calculation but by astute engineering, high skill level diving and due respect for the power of the ocean, scientists are still able to explore these alien environments and return with treasures from worlds other than earth that helps all mankind.